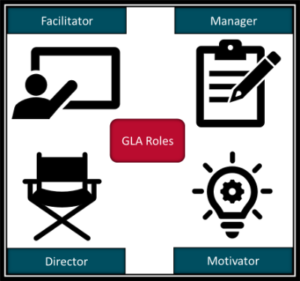

Graduate students working as lab assistants (GLAs) fill an important role in the laboratory-based educational experience. Laboratory-based courses contribute to student learning by providing opportunities to practice inquiry and experimentation that supplement traditional lecture courses. Thus, the primary role of the GLA is to facilitate and guide students through an authentic inquiry experience. To do this, GLAs manage the execution of the lab, facilitate inquiry-based learning, direct students towards successes, and motivate students by enhancing their experiences and outcomes.

The Inquiry-Based Approach

What is inquiry? Lab courses provide opportunities for students to learn through inquiry and experimentation. In contrast to instructor-driven approaches that focus on memorizing facts and concepts, inquiry-based laboratories take a student-centered approach that directly engages students with disciplinary practices. They also allow students to conduct authentic investigations to explore their own curiosities. This means that students are directly involved at each step of the inquiry process. In inquiry labs, students design experiments to answer open questions, make sense of their findings, and communicate those findings in a way consistent with disciplinary practices.

Benefits of inquiry: By its very nature, inquiry-based laboratories promote higher-order thinking skills. In labs, students apply knowledge of concepts and theories to design investigations and interpret meaning from their findings. Inquiry-based laboratories also promote a highly collaborative learning environment. Students often work in groups and engage in social aspects of knowledge formation. Inquiry labs also promote failure, which is important for learning. Research shows that it is important for students to grapple with and learn from failure in experimental design to understand the nature of science.

Additional Resources:

- How Students Learn: Science in the Classroom (National Research Council)

- Inquiry-Based Learning (PDF) (University of Wisconsin)

- Instructor’s Guide to Process-Oriented Guided-Inquiry Learning (PDF) (Pacific Crest)

The GLA’s Role

All GLAs in inquiry-based laboratories share some common roles across disciplines. In each of these roles you have the opportunity to contribute to the success of students by impacting their laboratory learning experience. Further, there are evidence-based best practices that you can use to increase your effectiveness in your role. In this resource we break this role into four distinct (albeit overlapping) parts: the GLA facilitates learning, manages operations, directs behavior, and encourages student motivation to learn.

Keep reading for more information about each of these roles, and recommended strategies for success. For additional reading, consider this resource on Teaching as a Laboratory TA.

The Facilitator: Facilitating Inquiry-Based Instructions

The Facilitator might be your most important and recognizable role in inquiry-based laboratories. As a facilitator, you guide students through the learning experience by asking effective questions, engaging in active listening, allowing for productive struggle, providing effective feedback, and addressing misconceptions.

Click to expand items below for practical strategies and best-practices associated with each part of the GLA’s “Facilitator” role.

Ask Questions Effectively

Asking effective questions is a student-centered instructional approach that works well in many contexts, including typical inquiry-based laboratories. As a facilitator of inquiry, you must be able to ask effective questions that promote reflection, metacognition, and empowerment among your students. Asking effective questions in inquiry-based laboratories can help you recognize student misconceptions, gauge their level of understanding, identify inconsistencies in thought, and foster engagement within the class. Asking effective questions takes practice, but when executed appropriately can be of benefit to both you and your students.

Strategies for Asking Questions Effectively

- Give students time to process your question and come up with a response. Don’t rush them, but slowly count to five or ten in your head before repeating or clarifying your prompt.

- If students are not able to provide you with a response to your question, do not simply provide it for them. Instead, ask them a question about their thinking, or prompt them to take a guess. This will help you identify what might be causing them difficulty.

- When asking a complicated question in a larger group, give students 60 (or more) seconds to take some notes and think it through, before asking for responses.

- Provide students with the opportunity to agree or disagree with a response that has been given, before you weigh in yourself.

- Acknowledge students’ answers and good thinking (even if they provide an incorrect or mistaken response). Your goal is to encourage their thinking and to create an environment where students feel comfortable participating in the conversation with you and with their peers.

- When a student provides an incorrect or incomplete answer, ask for more information. For example, you might say “That’s not quite right. Can you tell me more about what you’re thinking?” or “That’s not quite right. Can someone else help us out with another idea?” This will help you to uncover where a student’s reasoning may have gone wrong, and will allow you to correct the root of the misunderstanding. It will also help to create a safe environment for students to attempt an answer without the requirement that they always get it right.

- Create low or no stakes formative assessments to identify common misconceptions.

- Ask different students to respond to questions you ask.

- Vary the cognitive complexity of your questions. While it is important to ask low-level questions to uncover student understanding, higher order questions allow you to dig deeper, assessing students’ application, analysis, and evaluation.

- Do your best to only ask one question at a time.

- Reflect on your use of questions to facilitate learning. Make notes for yourself about what to do differently next time.

- Consider the types of questions you use, and how those questions can serve a specific purpose for their learning. For example,

- Ask probing questions to explore student misconceptions. For example, use questions like, “Why do you think that?” or “What experiences do you have that led you to think that?” to probe for misconceptions.

- Ask students to predict outcomes before engaging in an experiment, or to consider what might happen if conditions were different. For example, “What do you think would have happened if the temperature were turned up?”

- Ask students to explain their reasoning.

- Ask students questions that force them to reflect on what they are learning or what they have learned.

- Ask students to trace or describe connections between ideas or concepts.

Engage in Active Listening

Active listening is an important aspect of facilitating inquiry-based laboratories. Through active listening, you can identify where your students currently are in their learning and then chart a plan of action to best help them progress. Active listening is a requirement of asking effective questions (see above), and it provides a way to empathize with students and truly comprehend what they are thinking and saying.

Strategies for Active Listening

(adapted from Greater Good in Education)

- Give nonverbal acknowledgements (e.g., eye contact, head nodding, relaxed posture) when listening to your students. Nonverbal communication can signal to your students that you are engaged and interested in what they are saying.

- Paraphrase what your students say. Paraphrasing shows your students that you are paying attention and understand what they are saying. For example, you can say “If I understand what you are saying…” or “It sounds like…”.

- Focus on understanding what the student is saying rather than rushing to form a response. Try not to interrupt the student before they have finished expressing their thoughts.

- Aim for a comfortable physical distance that respects your students’ personal space but avoids the need to speak with a raised voice.

- Ask clarifying questions to help unpack what your student is saying. For example, “What do you mean when you say the expert?”

- Avoid expressing judgment or offering unsolicited advice. Focus on what the student identifies as their question or need.

Additional Resources:

- Active Listening (UGA Athletics)

- Why Listening Matters For Leaders (Inside HigherEd)

Allow Productive Struggle

Research shows that there is value in your students struggling and, yes, even sometimes, failing to get the results they are after. Struggle and failure are an integral part of authentic inquiry. Yet, at the same time, we do not want our students to become frustrated or lose confidence. Facilitating laboratories requires a delicate balance between telling students what to do and letting them struggle. As a result, your goal should be to act as a “guide on the side” – where you lead your students towards successes or solutions while encouraging independent thinking.

Strategies for Productive Struggle

- Ask questions to help students identify where they are stuck. One way to do this is to ask students (individually or in groups) to articulate their “Muddiest Point”. This can help you recognize where your students need the most help.

- Encourage reflection after a struggle or failure. Instead of simply telling students what they did wrong, have students journal or reflect about their learning experience. This can be a powerful strategy that allows them to create mental models and connect new ideas with prior knowledge in meaningful ways.

- Reduce your students’ frustration through coaching and active listening (see above). As an engaged GLA you should aim to actively listen to your students’ frustrations and then guide them to a solution.

- Tell your students about your own experiences with struggle or failure in research or inquiry. Your experiences can help to normalize student concerns and frustrations when things do not go as expected in the laboratory.

- Continuously circle the classroom and interact with all groups. By spending equal time with each group, you can address concerns and misconceptions and guide students towards success.

Additional Resources:

- Henry, M.A., Shorter, S., Charkoudian, L., Heemstra, J. M, & Corwin, L. A. (2019). FAIL is not a four-letter word. A theoretical framework for exploring undergraduate students’ approaches to academic challenge and responses to failure in STEM learning environments. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 18(1), ar11 1-17, https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-06-0108.

Provide Effective Feedback

Feedback is a crucial part of the learning process. When leveraged effectively, it serves to improve student performance, correct misconceptions, and encourage growth. Effective feedback from GLAs can help guide students through the inquiry process and help improve performance on assignments. We typically provide feedback in written or verbal form, but it is helpful to keep in mind that your own body language and gestures will also serve to provide information and cues to students. Overall, the goal is to provide students with information that is targeted and actionable: focus on the most critical areas for change, and make sure it comes with a suggested concrete action. In addition, be sure to offer feedback with kindness and respect, remembering that students are still learning.

Strategies for Providing Effective Feedback

- Aim to provide feedback on student work in a timely manner, so that your comments will connect with their thinking before they have moved on from the work they submitted. Students should have the opportunity to use your feedback to help them develop and grow in your course.

- Provide immediate feedback to students by circling the room while students are working, and engaging them in conversation. As explained in the Facilitator section above, focus on providing feedback and direction without simply telling them the answers or solving their problems for them.

- Frame your feedback in ways that are actionable for the student. Identify a specific next step for the student to take or a prompt for them to reflect on.

- Provide enough detail in your feedback to help your student clearly understand what you are saying, but not so much as to make it overwhelming. If you’re not sure, ask your students for feedback on your feedback!

- Focus your feedback on the highest priority items. This will help your feedback to remain manageable for your students without overwhelming them. Targeted feedback will lead to many small improvements over time.

- Don’t just focus on areas for growth or correction: also provide feedback indicating areas of strength and/or well-done work as well.

- Adjust your mindset to view feedback as an opportunity to contribute to the growth of your students – instead of simply aiming to correct all of their mistakes. This will help you provide thoughtful and encouraging feedback that helps students learn.

- Be specific in your feedback. For example, instead of just marking something as “good” or “bad”, tell them what it is that makes it good/bad. This will help students identify which behaviors to change or maintain over time.

- Use a grading guide or rubric to help increase your efficiency and consistency when providing feedback. If your supervisor has not provided something for you to use, try creating something and sharing it with them. This will also allow them to give you some feedback on what you are doing – thus hopefully also leading to your own growth!

Additional Resources:

- Frisbie, D. A., & Waltman, K. K. (1992). Developing a personal grading plan. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 11(3), 35-42.

- Receiving and Giving Effective Feedback

- Feedback for Learning

The Manager: Executing the Laboratory

The Manager role is foundational to the success of a laboratory course. GLAs are responsible for safely and effectively executing laboratory sessions. To do this, you must demonstrate and promote safe practices, help manage your students’ use of their time, arrive prepared to teach, and manage group dynamics.

Click to expand the items below for practical strategies and best-practices associated with each part of the GLA’s “Manager” role.

Promote Safe Practices

Teaching laboratory courses presents inherent risks that are not present for instruction of traditional courses. In laboratory courses, students interact with unfamiliar instruments, materials, chemicals, and organisms. Therefore, it is your responsibility as a GLA to promote safe practices in the laboratory.

Strategies for Promoting Safety

For Yourself

- Familiarize yourself with emergency protocols and the location of safety equipment in your laboratory classroom. Be prepared to act in the event of an emergency.

- Walk around the room and check in with your students, correcting inappropriate handling or use of equipment.

- Do not leave the laboratory unattended. If you need to step out for a moment, try to find another GLA, lab manager, or lab coordinator to supervise your class. When that is not possible, communicate your expectations for your students while you step away, and let them know when you’ll be back.

- Model good practice for your students. For example, you should demonstrate proper handling of equipment and the proper use of PPE.

For Your Students

- Communicate safety and emergency protocols to your students.

- Provide students with specific and detailed instructions for safe practices. Take time to walk your students through proper handling of materials and equipment. Assume that students do not know how to use equipment and set clear expectations regarding safety to your students (e.g., technology use or food/drink).

- Encourage students to maintain cleanliness. Accidents can be limited by maintaining clean areas.

- Share your expectations for students while they are in the laboratory (e.g., whether or not students should ask you before leaving the room).

Ask Your Supervisor

Some safety measures are specific to your discipline and/or laboratory classroom. It is important that you talk to your supervisor about these specific protocols.

Here are some suggestions of questions to ask your supervisor regarding safety:

- What are the emergency procedures specific to your classroom? (See Classroom Preparedness Checklist)

- What are potential hazards, dress codes, food, drink, and technology policies for our building / classroom / laboratory?

- Who are our emergency contacts specific to our laboratory?

- How does our laboratory meet students’ needs in terms of classroom accessibility?

Manage Students' Time

In inquiry-based laboratories, students learn by doing. One challenge with this is the need to ensure that students have sufficient time available to engage in the learning process. It is often your responsibility as a GLA to maximize time available for your students to engage in inquiry.

Strategies for Managing Students’ Time

- Plan out time for activities and lessons before class. It often helps if you walk through the laboratory as a student to determine the appropriate timing.

- Set clear time expectations to your students. For example, you could write time checkpoints on the board that outline your expectations and keep your students progressing throughout the lab.

- Evaluate the situation to determine whether time constraints permit productive struggle. To best manage students’ time, you should judge whether a direct response is more appropriate, or if you allow time for students’ productive struggle.

- Create low or no stakes pre-lab activities (e.g., quizzes or readings) to reduce the time spent lecturing during laboratory. Pre-lab activities can ensure your students come to laboratory prepared with the appropriate background knowledge. For example, you can use a student response system (e.g., TopHat) as a no stakes way to gauge student understanding before a laboratory class.

- Provide a 5-minute lesson to address common misconceptions. This short lesson will help students avoid wasting time with common mistakes.

- Design an Exit Ticket activity to address student questions and understandings before leaving the lab. Address student questions or concerns from the previous lab in an email or at the beginning of the next class.

Ask Your Supervisor

There will be context-specific differences in the amount of time you might be able to spend engaging students in formative assessments and/or offering short (e.g., 5 minute) lessons.

Here are some suggestions of questions to ask your supervisor regarding time management:

- Is there enough time in each laboratory class to implement formative assessment or a short (5-minute) lesson?

- Is there a suggested time break down for the different activities?

Prepare to Teach

Efficient management requires sufficient preparation. By taking the time to acquaint yourself with the goals for a lesson and to develop a plan, you will increase your effectiveness and decrease both your stress and the stress of your students.

Strategies for Effective Preparation

- Identify learning outcomes for each laboratory and communicate them with your students. Well written learning objectives are beneficial to instructors and students. See the Guide for Creating Learning Outcomes for more information about how to write effective learning outcomes.

- Anticipate student misconceptions and struggles. You can anticipate misconceptions and student struggles by running through the lab yourself or consulting with former or veteran GLAs who previously taught the lab.

- Practice using the equipment and materials. You should be able to demonstrate safe handling of equipment and materials, and thus, you should be familiar with the equipment your students are being asked to use.

- Brainstorm potential probing questions that can be asked to promote deeper engagement.

- Brainstorm possible questions that your students might ask during lab, and prepare to answer. You might also ask an experienced GLA or your supervisor for their experiences with common misconceptions among students.

Ask Your Supervisor

It is important to recognize departmental requirements may influence preparation requirements.

Here are suggestions of question to ask your supervisor about preparation requirements:

- Do we have prep sessions (e.g., wet labs) every week? What is required of me in these prep sessions?

- Will I have an opportunity to practice the laboratory before teaching?

- How early can I arrive before my class?

- What is required of me to set up the lab?

- Do we have learning objectives for each class?

- Can I discuss with returning or veteran GLAs to help identify potential pitfalls and issues?

Manage Group Dynamics

Inquiry-based laboratories are inherently collaborative and interactive. Students often work in groups or with partners in ways that mimic authentic settings and workplaces. Inquiry-based laboratories promote cooperative learning, which is a type of student-centered instruction. Cooperative learning is more than just having students work in groups on activities. For learning to take place, students in groups must have interdependence and accountability, and must be engaged in interactions. To be effective, GLAs sometimes need to manage group dynamics and promote effective cooperative learning among their students.

Strategies for Managing Group Dynamics

(Adapted in part from Winter et al., 2002)

- Promote individual accountability within groups by asking probing questions to all group members and designing activities where all group members must summarize their ideas.

- Spend equal time with each group. Sometimes it is easy to get “bottled up” with one group and inadvertently ignore the others. Simply circling the lab and asking groups “Is everything ok?”, can spark groups to ask questions and share concerns.

- Observe each group and their interactions. Are the group members interacting? Do you notice that one person dominating the discussion? These are signs that the group members may have a problem that needs addressing. For example, if you notice a group is not interacting with one another, you can assign roles to group members that reduce conformity and push the group intellectually (e.g., devil’s advocate, doubter, the fool). For more strategies for managing group dynamics see Challenges of Group Work (Carnegie Mellon) and Resolving Group Issues (University of Queensland).

- If group make-up will remain constant throughout the semester, check in with your students regularly about their group dynamics. You can do this by building in some no-stakes surveys for individuals to report how their group is working together and comment on any issues. By asking early and often, as opposed to at the end of the course, you can address issues as they arise.

- Create an open-door policy where students are encouraged to come to you with any group-related issues.

- When used early in the semester, begin pair and group activities with an introductory task that helps students get to know one another.

- Create opportunities for students to provide each other with feedback on their work.

- Create a space in class or online that is social or fun. For example, you might include a weekly “share a meme with your neighbor” activity, or some other short and light-hearted engagement opportunity.

Ask Your Supervisor

Logistics and specificities of group work in inquiry labs often differ by disciplines. For example, some disciplines may only work in pairs, while other disciplines work in rotating groups of 3-4.

Here are suggestions of question to ask your supervisor about managing group dynamics:

- How many group members are allowed per group?

- Do we change groups throughout the semester?

- What is the protocol for addressing issues in groups?

Additional Resources:

- Using Cooperative Learning Groups Effectively

- Developing Students’ Group Work Skills in the Laboratory Class (University of Michigan)

- Using Group Projects Effectively (Carnegie Mellon University)

The Motivator: Enhancing Student Experience and Outcomes in Lab Courses

The Motivator role is related to the ways in which a GLA can inspire students’ engagement and attention – even leading to longer term learning, retention in the field, and more. In the inquiry-based laboratory, motivated students will engage in discussion and problem-solving with their peers, come prepared to work, and leave able to articulate at least some of what they have learned.

One useful way to think about student motivation is in terms of Expectancy and Value Theory. In the context of student motivation, expectancy – or a person’s level of expectation that they will achieve a desired outcome – refers to both the belief that something can be successfully completed, and the belief that if you put the work in, you will be sufficiently rewarded. Student motivation to engage in the learning process increases and decreases in line with these types of beliefs. Value theory ties in as an additional lever for motivation: by helping students recognize value in learning activities, you can help increase their motivation to engage and learn. To learn more about different theories of student motivation, take a look at our primer on The Theory and Practice of Student Motivation.

Click to expand the items below for practical strategies and best practices associated with each part of the GLA’s “Motivator” role.

Encourage Growth Mindset

Carol Dweck’s research on growth vs. fixed mindsets has been widely discussed in academic settings (Dweck, Walton, & Cohen, 2014). Students with a fixed mindset toward their academic pursuits believe that their intelligence or talents are already determined and limited in quantity. They tend to give up easily and are demotivated or embarrassed in the face of challenge.

Students with a growth mindset, on the other hand, believe that their intelligence can increase and develop as they put effort into their learning. They tend to engage with resilience and independence, and learn to see risk and failure as opportunities for learning and development.

Finding ways to help students adopt a growth mindset in your class, then, can help keep students motivated and can thereby positively impact their learning.

Strategies to Encourage Growth Mindset

- Express belief in your students’ potential for continued learning and development.

- Help students explore, identify, and apply their strengths. This could be through a formal strengths-identifying tool, or simply by providing them with reflection questions to consider in light of their engagement in your course.

- Provide feedback that emphasizes areas for growth rather than simply identifying incorrect responses (which is also sometimes necessary).

- Ask students to reflect on their own work and progress, thinking about their approach to work in the course, and how they might need to adjust their strategies to find success.

- Emphasize learning and developing proficiency rather than performing well. If a student wants to improve on a test score, for example, talk through what the score represents in terms of their journey toward proficiency and content mastery, rather than the grade itself. What skills can the student develop further? How can they more effectively demonstrate their learning and understanding when answering a test question?

- Highlight the long-term implications of the course goals and skills, such as how students might incorporate them in future careers or interpersonal relationships.

As an added bonus, you can also work toward a growth mindset in your teaching. Remember that your teaching skills and knowledge can grow and change over time. When faced with situations that do not seem to be working out the way you’d like, engage in reflection and take the time to identify new strategies to apply.

Additional Resources:

- Dweck, C. S., Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2014). Academic Tenacity: Mindsets and Skills that Promote Long-Term Learning. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

- Growth Mindset and Enhanced Learning (Stanford University)

Provide Opportunities for Choice

By giving students choice in the laboratory — such as choice with experiments they study, the organisms or materials they work with, the peers with whom they work, and so on — you can increase their engagement and motivation. Choice provides agency, and allows students to take an active role in their learning process, and communicates to them their value (Brooks & Young, 2011). As a GLA, providing your students opportunities for agency in the laboratory can empower them to take ownership of their own learning and follow their curiosities.

Take care when allowing students to choose their own groups: some students will be uncomfortable with this (for a variety of reasons) and choosing groups can lead to a lack of useful idea exchange between diverse individuals. If you allow students to select their own groups, be sure to put processes in place to help those who are uncomfortable with the prospect of selecting a group, and look for additional opportunities for students from different groups to interact with one another.

Strategies for Providing Opportunities for Choice

- Provide choice of which assignment(s) to complete. For example, allow students to select from a menu of options.

- Provide choice in the order in which students proceed through activities.

- Provide choice for how your students demonstrate evidence of their learning. For example, when students report their observations, you could allow them to choose how they do so (e.g., with drawings, bullet points, paragraphs).

- Collaborate with your students to create rubrics for assignments.

- Allow your students choice in the inquiry process. One way to do this is to allow students to design their own questions and experimental designs.

- Listen to your students and be responsive to their feedback and concerns.

- Allow your students to work at their own pace when possible. Keep your students progressing through the lab, but build in freedom – where appropriate – for your students to move at the pace most conducive to their learning.

- Frame lessons within a context of your students’ interests, goals, and values.

Ask Your Supervisor

Logistics and specificities of providing choice in inquiry labs often differ by disciplines. For example, some disciplines may not build in opportunities for choice while others allow students to design their own experiments.

Here are suggestions of questions to ask your supervisor about providing opportunities for choice:

- Are there options for alternative assignments?

- What are the limitations for student choice in our lab?

- Can students choose their own groups?

- Is it appropriate to build in opportunities of choice for how students demonstrate their learning?

Additional resources:

- Brooks, C. F., & Young, S. L. (2011). Are Choice-Making Opportunities Needed in the Classroom? Using Self-Determination Theory to Consider Student Motivation and Learner Empowerment. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23(1), 48-59. (access here (PDF))

Connect Content to Interests

Connecting content to student interest makes a difference in student engagement and motivation because it helps grab your students’ attention. Students will find value in content that is meaningful to them and aligns with their own values. As a GLA, it is important to help students find these connection points. Doing so, can increase their motivation and engagement in your course. For example, imagine you have a student that is primarily interested in getting a job after they graduate. Your role as “The Motivator” could be to help your student make the connection of how doing well in this lab will give them a new skill or experience to talk about in future employment interviews.

Strategies for Connecting Content to Interests

- Connect practice to real world applications. Find connection points with your laboratory to student’s everyday lives.

- Provide context and the overall picture to your students. Tell your students why what they are doing is important / relevant. While students may be investigating a specific phenomenon in lab, your role as a GLA is to provide the context that is meaningful to your students. For example, a physics GLA could relate a laboratory on circuits to the circuits used to run computers, phones, and technologies that students interact with every day.

- Connect laboratory practice to content learned in lecture. This will be easy to do for lab courses that are built to connect directly to lecture. However, it is also possible to connect what is learned in lecture in standalone laboratory courses. To do so, ask your student’s what they are learning in lecture, or request a syllabus from the lecture instructor.

- Connect laboratory practice to student interests. Research shows that tying educational experiences to student interests increases motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes for your students.

- Tell your students about a cool new discovery that is directly related to the content or practices they will be doing in lab that day.

- Connect content and learning activities with things that you find particularly interesting about the work. Don’t be afraid to let yourself gush a little bit about your own research and/or your love for the discipline!

Build Relationships

The word relationship has origins derived from the Anglo-French word relacioun, meaning “the act of telling.” Therefore, by actively telling your students that you care, through your words and actions, you can start to build your students’ intrinsic motivation to learn in your laboratory. Research shows that two relationships are most important to cultivating intrinsic motivation: student-student and student-teacher relationships. To help facilitate student-student relationships, you can create a learning space that values and emphasizes interactions and discussions among peers. It is also important that you build your own relationships with your students – as you are the leader in the classroom.

Strategies to Build Student-Student Relationships

- Incorporate small group work frequently. Small groups provide a space for students to build relationships and share ideas with one another. By its very nature, inquiry-based learning promotes small group learning and project or problem-based learning.

- Use active learning strategies, when possible, to promote discussion. Activities like “Think Pair Share” to invite students’ own ideas and provide a space for them to share them with their peers.

- Encourage students to provide specific praise of their peers in your laboratory. For example, providing a space at the end of class for your students to highlight their peers can start to deepen relationships among your students.

- Provide opportunities for students to share their interests, values, and goals with their peers early on in the semester.

Strategies to Build GLA-Student Relationships:

“If the relationship between the teacher and the students is good, then everything else that occurs in the classroom seems to be enhanced.” (Marzono, 2007)

- Take time to learn about your students’ interests, values, and career goals. By doing this, you are not only building the roots of a relationship, but you can also use this information to better cater the content to student interests.

- Learn names and correct pronunciation. Learning students’ names and using them frequently shows your students you care about them and you see them as an individual.

- Provide praise for successes.

- Practice empathy. Communicate consideration for other events going on in students’ lives (e.g., major exams in other courses, extracurriculars, personal issues)

- Be flexible when possible.

- Have students create name placards to place on their desk during each class. Invite them to decorate them in whatever way they’d like, as an opportunity to showcase their personality and interests along the way.

- Learn your students’ names and correct pronunciation.

- Encourage students to attend your office hours. When they do, consider asking them questions about themselves (e.g., what’s your major?). Avoid getting overly familiar or personal, but general inquiries or small talk can go a long way to establishing a positive relationship you’re your students.

- Create a questionnaire in advance or on the first day of class to get to know your students’ background. For example, ask them about their preferred name and pronouns, what they are hoping to learn in the class, their career goals, and so on. Use this information to help inform your interactions with them as the semester gets underway.

- Regularly check in with your students. A simple, “How is everything going” can a spark conversation and show your students you care about them. The time just before class starts, as students are arriving, can be a good time for this.

- Share information about yourself with your students. For example, you might tell them about a pet, or mention an outdoor space you like to visit.

Questions?

Please contact us via [email protected].

- Teaching Resources

- Active Learning

- Digital Learning Tools

- Establishing your Syllabus

- Evidence-Based Teaching Strategies

- Reflection, Feedback & Evaluation of Teaching

- TA Resources

- Teaching Amid Disruption

- Scholarship of Teaching & Learning (SoTL)

- Teaching & Learning Library

- Teaching Policies & Procedures