What is Universal Design?

The concept of universal design comes out of considering the needs of people with disabilities in city planning and architecture. The underlying idea is that there are ways of designing spaces and objects that make them maximally accessible and effective for everyone, including those with and without disabilities. A classic example of universal design in everyday life is curb cuts, which are ramps built into the curb of a sidewalk and were originally intended to benefit those who use wheelchairs. However, curb cuts also make sidewalks more accessible for people pushing baby strollers and carts, or those riding bikes, scooters, skateboards, etc.

Image: A person using a wheelchair, a person pushing a stroller, a person riding a bicycle, and a person using a skateboard all benefit from curb cuts on sidewalks that border roads.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Teaching

The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) model was proposed by Drs. Anne Meyer and David Rose at the Harvard School of Graduate Education in 1984 to address ways that teaching could be most beneficial for students with disabilities (Meyer & Rose, 2014). Over time, the model has become a focus for supporting the success and inclusion of all students served by educational institutions (Fovet, 2020). Just as curb cuts better meet the needs of all citizens, courses designed using the UDL model better meet the learning needs of all students, including those with different abilities and learning preferences, identities, and educational goals. David Rose describes the aims of the UDL as ‘tight goals, flexible means’ (Bacon, 2014), reflecting the fact that the model does not compromise on the rigor of learning goals or outcomes, but rather it varies the delivery of what is taught and students’ ability to demonstrate what is learned.

Resources for UDL & Teaching

- Center for Applied Specialized Technology (CAST): a cache of resources related to UDL, its application, and the empirical work supporting its value for student learning. Developed and maintained by Rose & Meyer.

- A UDL Course Inventory (PDF): a checklist to help you identify specific teaching strategies associated with increasing student success through the application of UDL.

What is the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Model?

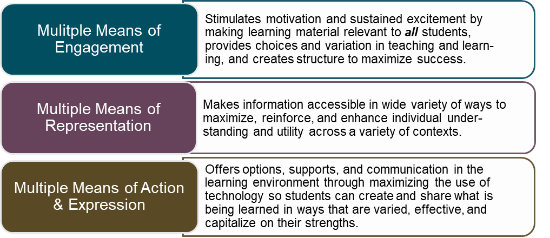

The UDL is organized into three broad instructional guidelines. Specifically, the model urges instructors to use multiple means of: 1) engagement, 2) representation, and 3) action & expression with respect to course content and design. A summary description of each of the three guidelines is below, and the full model can be found on the CAST website.